Frances Madden (orcid.org/0000-0002-5432-6116)

Posted 17 February 2021

Many of the case studies we have looked at so far in the Heritage PIDs project have focused on persistent identifiers (PIDs) for collection items and people associated with those items. However people are not the only entities that can be associated with items and which have authority files in museum, library and archive management systems, places are often added to management systems as authority files. In addition many systems contain large amounts of other location data e.g. location collected, place of publication etc. There has been interest expressed in PIDs for places and locations over the past several years. It was noted by the FREYA project’s landscape survey in 2018 and several tools have been developed for capturing PIDs for places, one of which is discussed here.

Locating a National Collection is another foundation project in the Towards a National Collection programme, which is investigating the role of location in relation to building a national collection. It aims to help organisations use location data to connect their collections and engage audiences in new ways. Within the project's objectives, they include 'understand how location is referenced and represented in IRO collections', 'scope and describe the technical components necessary to connect collections using location, the available options and make recommendations for potential paths to progress', and 'to develop and evaluate a prototype access interface to enhance our understanding of user requirements and potential case studies'. It is hoped that strengthening the connections between resources in GLAM institutions and places will help the resources resonate more with general audiences and the project is exploring the idea that concepts such as ‘place identity’, ‘locality’ and ‘proximity’ might be engagement drivers for users browsing collections.

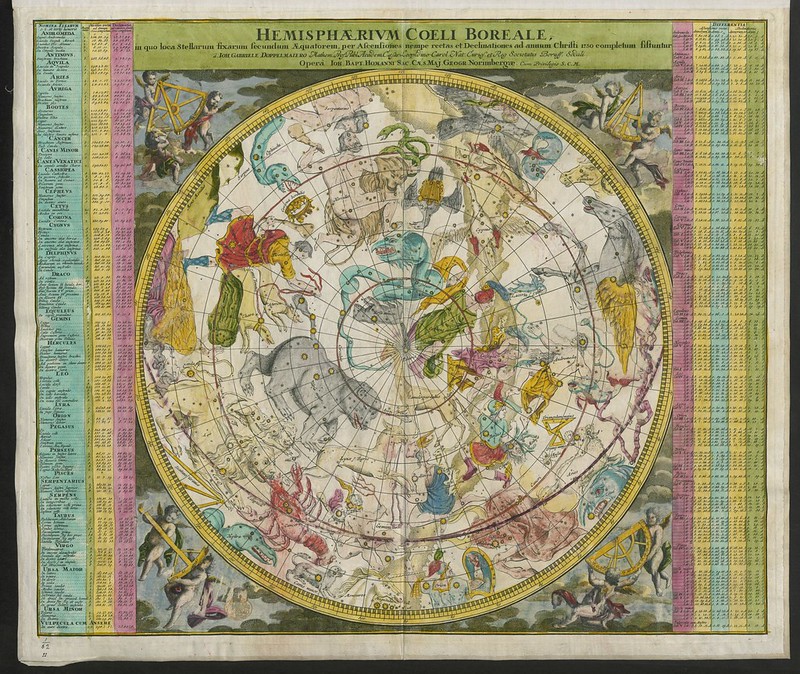

The BL King’s Topographical Collection:'Hemisphaerium Coeli Australe (Boreale)'

The BL King’s Topographical Collection:'Hemisphaerium Coeli Australe (Boreale)'The importance of location for a national collection is as a point of commonality across collections held by different organisations. If users are able to search across different collections simultaneously and find items related to a particular location, they can be used by both research users and the general public. At present conducting searches across different collections requires time, dedication and considerable skill on the user’s behalf. Organisations hold location data in their collection metadata but this is not in any standardised form across the sector.

For GLAM organisations, one of the main reasons PIDs are useful when dealing with location data is they help disambiguate between places which have the same name (e.g. Athens, Greece vs. Athens, Georgia) and can help with identifying the same place described using a different name either in different languages (Caerdydd and Cardiff) or because a place has changed name over time (Kingstown and Dún Laoghaire). Identifiers can be used to connect these concepts together so they can be understood to be the same, preventing data silos. Often cataloguing guidelines will have addressed these issues at the level of an individual system where standardised terms are used but these can change over time and many organisations will have more than one cataloguing system, e.g. one for library collections and one for archives, and these may not have the same standards. Once you start combining data from across heterogeneous systems and different organisations the problems increase in scale.

Note: The links in the examples connect to Wikidata examples to demonstrate how these variations can be understood, other identification methods such as gazetteers are described elsewhere in this post.

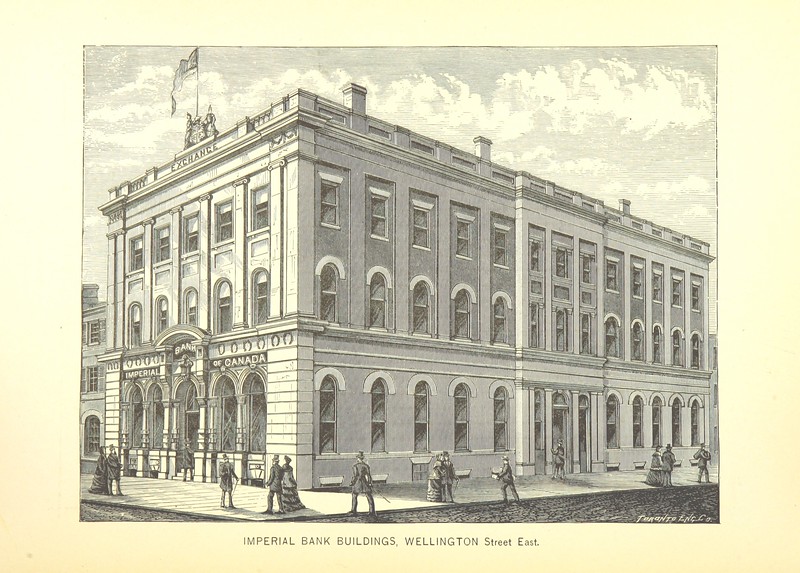

British Library digitised image from page 370 of 'Toronto: past and present: historical and descriptive. A memorial volume for the semi-centennial of 1884, etc'

British Library digitised image from page 370 of 'Toronto: past and present: historical and descriptive. A memorial volume for the semi-centennial of 1884, etc'Applications using location PIDs could include adding coordinates to create maps and other visualisations, understanding the movement of collection items and illustrating all collection items related to a particular place, increasing users’ understanding. One of the most successful examples of a research community within cultural heritage using identifiers, any identifiers - not just those related to location, is the Pelagios network. The network allows researchers and curators to work together to link and explore the history of places. To do this, they use online gazetteers which are a type of geographical dictionary, some of which have been made available in a linked open data format and therefore have uniform resource identifiers (URIs), or a sort of PID.

The Pelagios network created a tool called Recogito which allows you to tag place references contained in texts or images with gazetteer URIs, such as from Pleiades, and visualise them on a map. These URIs are connected in a standard way which can be exported in formats such as csv and RDF to be queried and analysed by researchers. This has been used in many research projects to investigate documents of interest (either textual corpora, archaeological collections or others) in a spatial perspective, gaining a new understanding of them and highlighting new perspectives but also disciplines such as cartography, see the Pelagios blog for examples. The Locating a National Collection project is building on this work and exploring the applicability of tools such as Recogito in augmenting collections with identifiers. The URIs used in a gazetteer like Pleiades can be resolved in both human and machine readable formats. While it is not necessary for them to be resolvable (a user can click on them and is directed to a webpage with metadata about the location) to link, it does make it easier for an end user to engage with them.

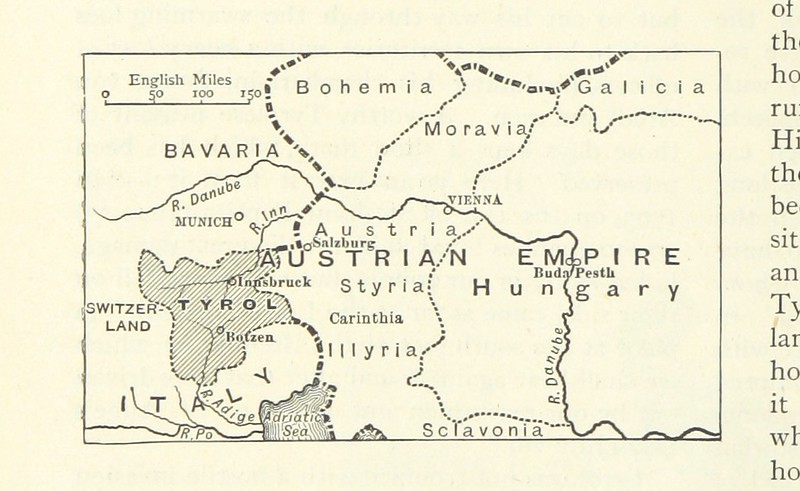

British Library digitised image from page 586 of 'Illustrated Battles of the Nineteenth Century, by Archibald Forbes, Major Arthur Griffiths, and others.'

British Library digitised image from page 586 of 'Illustrated Battles of the Nineteenth Century, by Archibald Forbes, Major Arthur Griffiths, and others.'There are several gazetteers available in linked open data format in addition to Pleiades and gazetteers have gained particular traction for scholars of the Classical world but their coverage is not uniform across time periods, e.g. there are very few for the Medieval period. Wikidata can also be used for this purpose, while not a gazetteer, it contains large amounts of location data in a standardised linked format.

However concepts of location can have the following issues which need to be addressed when assigning PIDs:

- Concepts of location can change over time. Collections can relate to items created at any point over thousands of years. Names of places change but also the boundaries which define a place can evolve. For example Wikidata provides an ID for Athens, the capital city of Greece but also for Classical Athens, the city-state in ancient Greece. These two concepts are related in Wikidata’s model but are not considered the same. Another example of evolving concepts of places would be how the boundaries of local government areas can change over time.

- Concepts of place can be ambiguous and it is not possible to determine to which place a text refers.

- The systems holding location data are diverse and they can manage location terms in different ways, e.g. some fields may be linked to authority records but some are not.

- Metadata is not standardised across organisations and concepts can be represented in various ways, using different terminologies and in diversely named fields. This makes it difficult to extract the information automatically.

- There can be many possible locations associated with a collection item, it can be difficult to determine if all of these should be connected to an item. At what point does it become too much for a human user to understand.

- There can also be a lot of location data missing from collection metadata due to minimal cataloguing practices.

- There can also be a lot of location data missing from collection metadata due to minimal cataloguing practices.

So what do cultural heritage organisations need to think about to start using location PIDs? For one thing, organisations should think about augmenting their existing collection information with external identifiers. Several of the case studies the Heritage PIDs project has looked at so far focused on the creation of PIDs for items in organisations’ collections. However, there are benefits to linking to collection items and other external entities from your own system. Another foundation project, Heritage Connector, is developing a tool to use Wikidata identifiers to do just that.

Scale is always an issue when dealing with large existing collections. How do you find all the related identifiers and add them into the collection management system? This issue has not been fully resolved but the Living with Machines project has developed tools to help with automated matching of terms which could be applied here. Some collection management systems can also struggle to support identifiers presented as resolvable links within them. For ongoing collecting, cataloguing staff would need to be trained on the appropriate use of these identifiers and best practice is still emerging on their use in cataloguing.

PIDs for location data probably provide one of the best success stories in terms of identifiers being used to facilitate innovative research, however there is no scheme as yet which can be adopted universally and in turn collection management systems lack the functionality to support location identifiers. Despite this, any organisation which is considering implementing persistent identifiers within their systems should definitely look at including their location data within the scope of that implementation and exploring ways to increase the interoperability of their collection data.